August 20, 2020

COVID-19: A personal experience

Watch our video interview with Jerry here.

Watch our video interview with Jerry here.

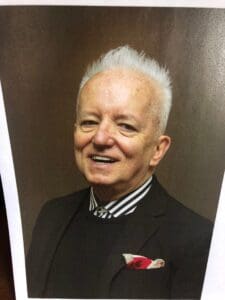

Jerry Brown, Covia’s Senior Director of Affordable Housing, has no idea how he got exposed to COVID-19. “Between March 12 and June 28, I probably saw less than 20 people total the whole time,” he says. Nevertheless, on June 28th, “I got a really bad upset stomach. I thought I probably had food poisoning. And that lasted a straight 48 hours, two days. And then that Sunday, I felt like an elephant was sitting on my chest. I could not get my breath.”

A trip to the emergency room confirmed his suspicions: he had COVID-19.

At first, the doctors thought he could be treated at home. “I thought I was doing fine for seven days. But the next Sunday, the elephant was sitting back on my chest again and just could hardly breathe at all.” After the hospital confirmed he had COVID-19, Jerry was admitted to the hospital to a floor designated for COVID-19 patients. “There were 70 rooms. All of these rooms are individual rooms that have special air filtering so that it doesn’t get into the rooms of the rest of the hospital,” Jerry explained. “I was lucky enough to get the last room that was available that night. I didn’t get in to my room until three o’clock the next morning, but I did get in there, and I felt so much better once the nurses and the CNAs all came around and started taking care of me.”

He thought he would be in the hospital just a couple of days, but ended up staying 10 days as his medical team determined what treatment regimen would work best for him. “They said, ‘We don’t really have a set treatment for this. Everybody is different. So what we’re going to do is just sort of throw things at you over the next few days to see what works for you.’”

Remdesivir proved unsuccessful, and his medical team was unable to get approval from the Federal Government for a plasma treatment. What ultimately worked was a steroid treatment. “The problem with the steroids and the reason that was [treatment] number three is because steroids don’t really work well with people who have diabetes.” Although Jerry’s diabetes is not severe and well controlled with Metformin, “when I started taking the steroids, which made me feel a lot better breathing-wise, my sugar levels went to 700. That’s the reason I had to stay in the hospital, so long. With that sugar level, I could have had a stroke or kidney problems.”

From the outset, his medical team told Jerry he had one goal: Stay out of the ICU! “They actually wrote it on the white board in my hospital room. There were 18 ICU rooms and they were full the whole time I was there. Over that 10 days, seven people died. You would hear that through the nurses and the medical staff and the doctors were very honest.”

Although he’s doing better, Jerry is not fully recovered. “I exercise my lungs. I speak through Zoom with a therapist. But we’ll see how it goes. Right now I’m breathing fine. I can walk about 40 feet before I get tired and need to sit down.”

He also knows that this is still a scary situation – and understands it, having lived through the AIDS crisis of the early 1980’s. “I came to San Francisco in 1979. I got transferred with my job to San Francisco, and it was right at the top of the AIDS crisis. So that was really scary for me. And we all know that that lasted a little while before we figured out that it didn’t need to be as scary as we thought because there were things you could do to make sure that you didn’t get it. I’m sure that’s going to happen with COVID-19 too. But this disease is a little different because it’s in the air. How do we manage that, other than with these masks and watching our hands and social distancing?”

He’s concerned at the number of young people who aren’t taking COVID-19 seriously. “I see so many people that aren’t wearing masks or social distancing, and that’s very scary for me. I saw a lot of that in San Francisco. I live on Nob Hill and the younger people were still playing basketball and not wearing a mask and running without a mask. Hopefully they will get over it, being young and having strong bodies and a good immune system. But there are so many people around them that could get COVID.”

Aside from practicing good infection prevention habits of handwashing, wearing a face covering, and maintaining your distance, Jerry wants to remind people that, whether it’s COVID-19 or any other illness, “you are your own best advocate for your medical care.”

While he was in the hospital, “Every night I would put my questions together about nine o’clock. I would think of everything I wanted to ask them, ‘Can I do this? Can I do that?’ And then I would have my questions ready. It made me feel better too, you know, just getting an answer to things I had questions about.”

He also advises everyone to update your health care and financial directives (such as wills or trusts) “now – not when you are in the hospital bed.” He also recommends purchasing an oximeter – a battery-operated finger device that gives instant reading of your pulse and blood oxygen levels. “One of the first signs of COVID is not enough oxygen in the blood. To be up walking at a natural movement pace the reading should be 90 or above. You can purchase at most drug stores or on line for around $30. I now check mine twice a day.”

The experience has made him reflect on the importance of connections. “I thought about the people from the 1918 flu. How awful. They didn’t have Zoom. They didn’t have the Internet. They didn’t have a way to connect to people. And even though I was in that room alone, I spoke with my family every day. We FaceTimed. I Zoomed friends. People dropped things off. I got cards and I was surprised they let flowers come to the room, and all of that made the experience. I had the feeling that people were caring about me. We figured out ways to connect with each other.”

All of us at Covia wish Jerry and all who are affected by COVID-19 connection and comfort during these difficult times.

Watch our video interview with Jerry here.